Written by Dr. Emily R. Thornton, PhD, LCADC , Last Updated: November 8, 2025

Emerging neuroscience research suggests potential avenues toward addressing certain addictions through targeted brain stimulation, though clinically validated cures are not yet available. A landmark 2007 study found that in a subset of cases, smokers with damage to the brain's insula region reported immediate cessation with minimal relapse. While experimental approaches like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) show promise, widespread clinical application remains years away.

Table of Contents

By both training and experience, substance use disorder (SUD) counselors treat addiction in all its forms as a chronic condition. It's a constant presence in the patient's life, requiring ongoing management and vigilance. Counselors train their patients to resist cravings, overcome triggers, and build resilience. But the question remains: can addiction truly be escaped permanently?

It's a practical approach in a world where relapse rates range between 40 percent and 60 percent on average. For chemically addictive substances like opioids, relapse can run as high as 91 percent.

This aligns with current medical understanding of addiction's sources. It's a complex mix of genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, and individual experience. No known treatments overcome all these contributing factors.

Most patients and counselors believe addiction can be beaten, but never permanently. Every day brings another challenge to manage the pull.

But what if that wasn't true?

Evidence Points to Where Addiction Lives in the Brain—and How to Stop It

The traditional view of addiction as a complex blend of environmental and genetic factors mirrors our understanding of various conditions. This includes autism spectrum disorder, Alzheimer's disease, and many forms of cancer.

Understanding that environmental and genetic factors both fuel certain diseases hasn't stopped efforts to isolate the physical source of those conditions in hopes of developing more effective treatments.

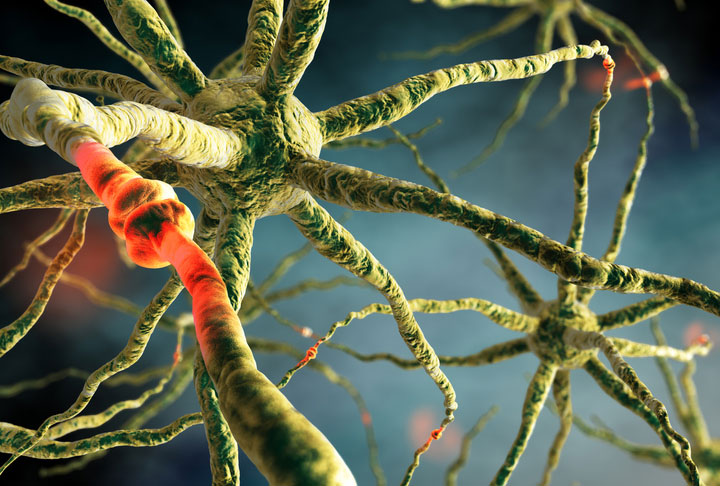

A landmark study published in Science in 2007 may point to the physical source of at least one form of addiction. Researchers at the University of Iowa conducted an analysis of cigarette smokers who experienced strokes that damaged the brain.

They found something remarkable. In a subset of these individuals, smoking cessation occurred immediately after the brain damage. These patients reported minimal cravings and showed significantly reduced relapse compared to smokers with brain damage in other regions.

The stroke damage had occurred in many different brain locations. The common connection among those who stopped smoking was that the damage involved a specific pattern of connectivity to the insula. This somewhat mysterious part of the cerebral cortex deals with consciousness, emotion, and the senses.

New Data Comes Together with Experimental Treatments to Show Potential

The study results offer a new target for a technique called TMS: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. TMS has been FDA-approved for treating depression since 2008 and OCD since 2018. However, it's important to note that TMS is not currently approved for addiction treatment and remains experimental in this application.

The technique involves non-invasive targeted magnetic stimulation that induces small electrical currents in the brain. It's a safer and more painless update on electroshock therapy. When applied precisely, it can produce cognitive changes.

Previously, TMS experiments in smoking cessation were largely by guesswork. Now, electrical stimulation targeting the insula network is being studied in research settings. While results are preliminary, they show potential for this experimental approach.

The Brain Has Long Been Seen as a Path to Addiction Therapy

Brain-altering techniques aren't entirely new in addiction treatment. Various FDA-approved medications have useful impacts on cravings. Bupropion helps with nicotine addiction while naltrexone aids alcohol recovery.

Chemical interventions typically work by blocking certain neurotransmitters. They create effects that only last as long as the chemical stays in the body.

Identifying brain connections that may be involved in addiction opens up potential non-chemical interventions. These might be more targeted than pills, though research remains in early stages.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation has the potential to affect the function of certain brain features. This is similar in principle to how stroke lesions work. That opens the door to investigating potential new approaches for some types of addiction.

Beyond Smoking: Implications for Other Substance Use Disorders

While the groundbreaking research focused on smoking and nicotine addiction, scientists are exploring whether the insula plays similar roles in other substance dependencies. Early evidence suggests the insula may be involved in alcohol cravings, opioid seeking behavior, and stimulant addiction.

The brain's reward pathways function similarly across different addictive substances. If targeted interventions can affect the insula's role in nicotine addiction, they might work for other substances too.

Research remains in very early stages for most substance types. Some clinical trials are exploring brain stimulation applications for alcohol use disorder and cocaine addiction. Results remain preliminary and not yet validated for clinical use.

The key question isn't whether brain stimulation works identically for all addictions. It's whether targeting the insula network offers a potential new research avenue for substance abuse counselors and their clients across multiple addiction types in the future.

Opening the Door to Potential New Treatments Sparks Debate in the Substance Abuse Treatment Community

To be clear, addiction is experienced by most people as a chronic disorder that requires ongoing management. The chronic disease model remains the evidence-based standard for treatment. Even if breakthrough treatments emerge, we're years away from any clinically validated approaches that fundamentally change addiction treatment.

If such treatments become available and validated, they could significantly impact the field of SUD counseling.

The idea of addiction as a chronic issue is deeply ingrained in current treatment approaches. There's a whole body of science and research on different types of relapse and stages of recovery. This framework acknowledges the reality of relapsing and helps patients maintain engagement.

The view of addiction as a chronic condition is useful as a psychological technique in treatment. With relapse a real and likely possibility, it's important to prepare clients for the risk. Reminding them that relapse is part of the process rather than a treatment failure keeps them engaged and motivated.

Some of the worst features of historical substance abuse treatment came from seeing addiction as simply curable. When a relapse occurred, it was viewed as a moral failing. This caused tremendous harm to patients.

There are strong, time-tested reasons to maintain the chronic disease model and keep relapses in perspective. Viewing SUD recovery as an ongoing process protects patients psychologically and aligns with current evidence. Until new approaches are thoroughly validated through rigorous clinical trials, this model remains the foundation of effective treatment.

Advanced Degrees Prepare Counselors for Research, Leadership, and Emerging Approaches

These complex debates are exactly why advanced credentials in addiction counseling require a master's degree in substance abuse counseling or higher.

Conducting research that builds data to inform treatment approaches is critical to addressing the American addiction crisis. It happens in doctoral studies like those in PsyD (Doctor of Psychology) or PhD programs in addiction counseling. Students spend up to half their four years on research and investigation. They're the individuals asking these questions and driving the answers.

While most counselor roles remain grounded in evidence-based behavioral and pharmacologic approaches, advanced education prepares professionals for research and leadership positions. It's through graduate-level programs that research results are evaluated, critiqued, and eventually translated into practice.

Master's programs deliver state-required training for certification and advanced skills in current evidence-based therapy techniques. They also encourage critical thinking about emerging research.

That critical evaluation is exactly what's needed as the field encounters potential breakthrough developments. If and when new treatments become clinically validated, it will be professionals with advanced training who can appropriately assess, implement, and refine these approaches while maintaining commitment to evidence-based practice.

Frequently Asked Questions About Addiction Research and Brain Stimulation

Is TMS currently approved for treating addiction?

No. TMS is FDA-approved for treating major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), but it is not approved for addiction treatment. It's being studied in research settings and clinical trials for smoking cessation, alcohol use disorder, and other substance addictions. Any use of TMS for addiction is considered experimental and off-label. Patients should consult qualified healthcare providers about evidence-based treatments.

Can brain stimulation cure addiction?

Currently, no. While research on the insula and brain stimulation shows promise, there are no clinically validated cures for addiction. The 2007 Science study showed associations between insular damage and smoking cessation in some stroke patients, but this doesn't translate to a cure that can be safely replicated. Brain stimulation for addiction remains experimental and unproven. The chronic disease model remains the evidence-based approach to treatment.

When will new addiction treatments be available to patients?

Clinically validated treatments based on brain stimulation research are likely many years away, if they materialize at all. Current experimental approaches must undergo extensive clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy before FDA approval. Even if trials succeed, the process of approval, standardized protocols, insurance coverage, and widespread availability takes years. Proven treatments like behavioral therapy, medication-assisted treatment, and support groups remain the primary evidence-based approaches.

Does this research change how counselors should treat addiction today?

No. The chronic disease model of addiction treatment remains valid, evidence-based, and effective. Counselors should continue using proven approaches, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, medication-assisted treatment, and relapse prevention strategies. While staying informed about emerging research is valuable for professional development, experimental approaches should not replace or diminish commitment to evidence-based methods that have demonstrated effectiveness.

What does this mean for the future of substance abuse counseling careers?

Advanced education at the master's and doctoral levels prepares counselors not just for clinical practice, but for research and leadership roles that evaluate emerging approaches. If new treatments eventually become validated, professionals with strong backgrounds in both neuroscience and clinical practice will be needed to assess, implement, and refine these approaches. However, the core of counseling will likely remain rooted in the therapeutic relationship, behavioral interventions, and support for long-term recovery management.

Key Takeaways

- Research on the brain's insula region suggests potential new directions for addiction research, though clinically validated treatments remain unavailable

- Brain stimulation techniques like TMS are experimental for addiction and not FDA-approved for this use, despite approval for depression and OCD

- The chronic disease model of addiction remains the evidence-based standard and should guide current treatment approaches

- Advanced education at the master's and doctoral levels prepares counselors for research and leadership roles in evaluating emerging approaches while maintaining commitment to proven treatments

- Until new approaches undergo rigorous validation, evidence-based behavioral and pharmacologic treatments remain the foundation of effective addiction counseling

Build Your Foundation in Evidence-Based Addiction Treatment

As the field evolves, advanced education prepares you to evaluate emerging research while mastering proven treatment approaches. Explore degree programs that combine neuroscience with evidence-based practice.

Medical Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment recommendations. Always consult with qualified healthcare providers regarding treatment decisions for substance use disorders. The brain stimulation approaches discussed remain experimental and are not FDA-approved for addiction treatment. The chronic disease model remains the evidence-based standard of care.